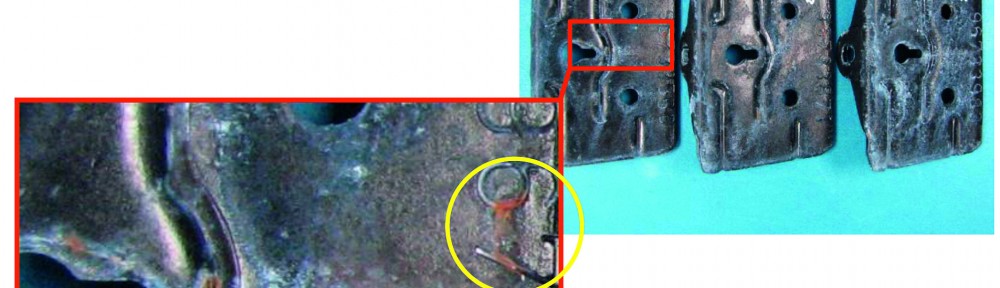

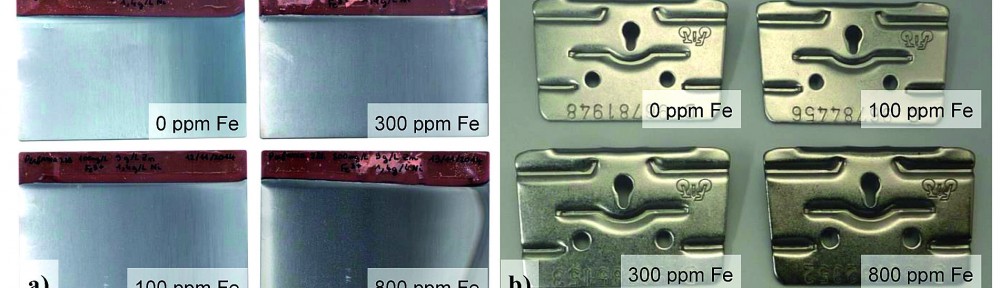

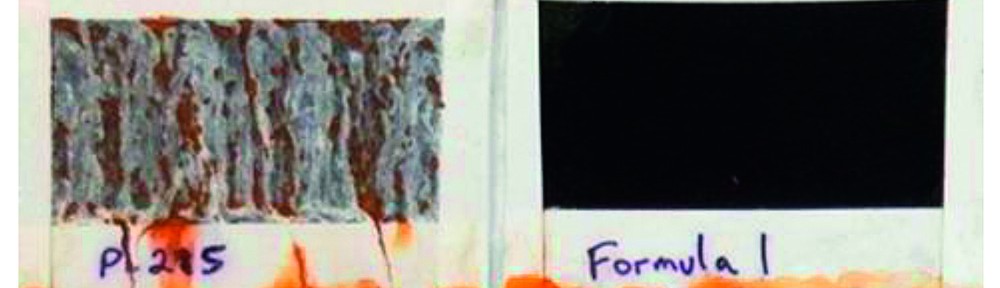

Electrodeposited zinc-nickel coatings are broadly used as sacrificial coatings for steel since many years in the automotive industry and for other high corrosion resistant applications. The best corrosion resistance is obtained with ZnNi deposits having 12–15 % Ni in the alloy. Many studies were performed showing the influence of nickel content in the alloy [1]. In industrial plating electrolytes other metals than Zn and Ni can be present. In alkaline zinc-nickel electrolytes mild steel is usually used as anode material. Depending on electrolyte composition and plating conditions more or less iron can be dissolved by anodic dissolution into the electrolyte. It is well known that the iron is codeposited into the zinc nickel alloy, but the effect on the alloy properties was never systematically investigated. In this study the influence of up to 800 mg/L iron in commercially used alkaline zinc nickel processes is investigated. Up to 8 % iron is amorphously codeposited in the alloy. No new iron containing phases could be detected by X-ray diffraction (XRD). ZnNi g-phases (Ni2Zn11/Ni5Zn21) are still the dominant phases, but plain orientation can be affected by iron codeposition. Corrosion properties are investigated by electrochemical measurements and neutral salt spray test. Whereas no huge difference in the corrosion properties between the bare ZnNi and ZnNiFe coatings was observed, the corrosion resistance with a subsequent trivalent chromium passivate can be drastically improved using iron in the alloy.

JEPT – Journal for Electrochemistry and Plating Technology

Edited by: DGO-Fachausschuss Forschung – Hilden / Germany